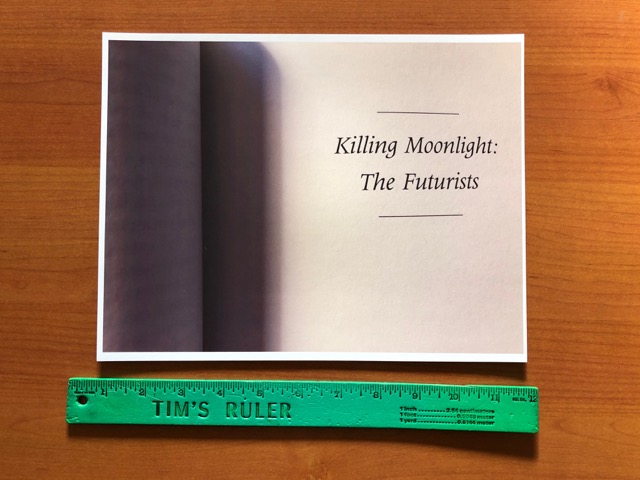

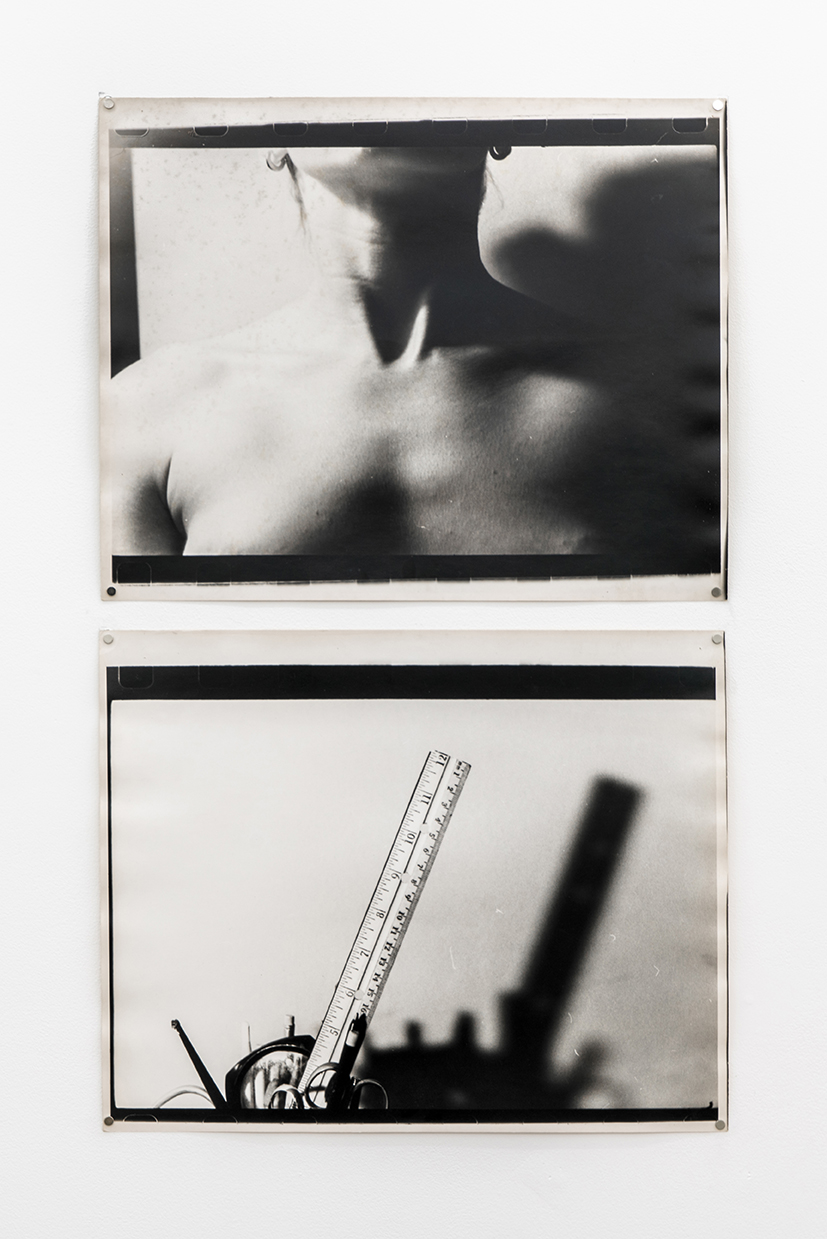

Tim's ruler

| Gallery

Tim Maul

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

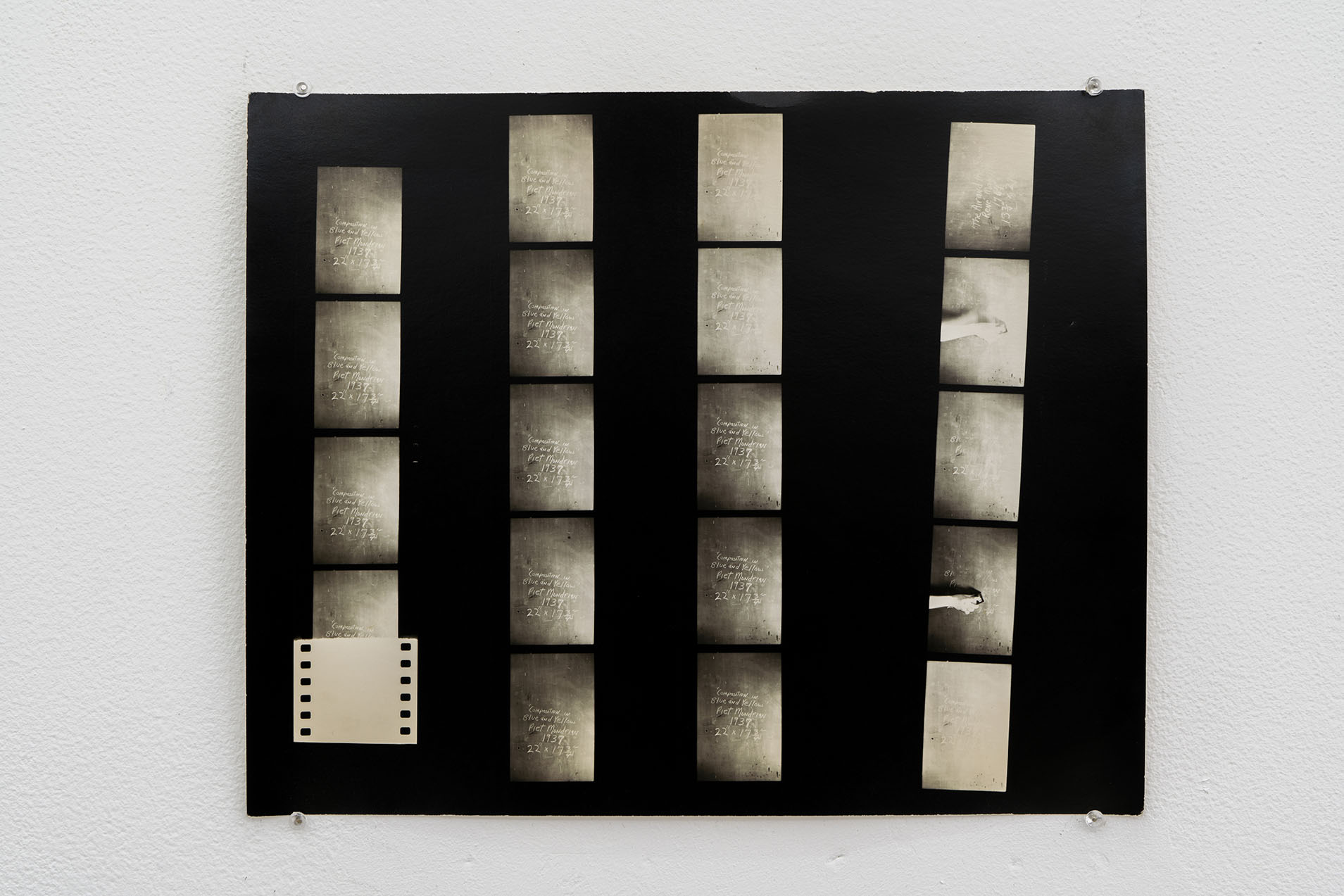

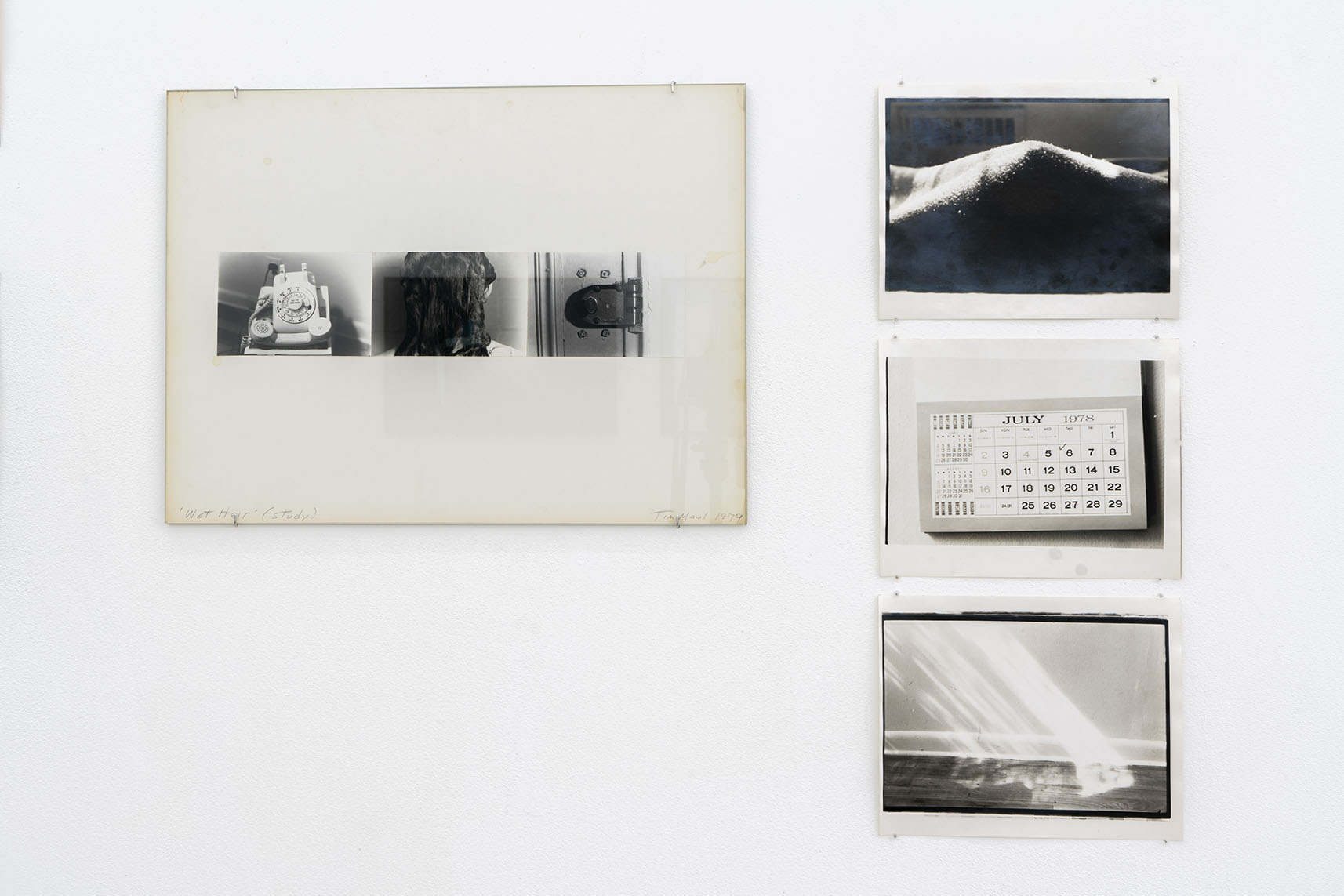

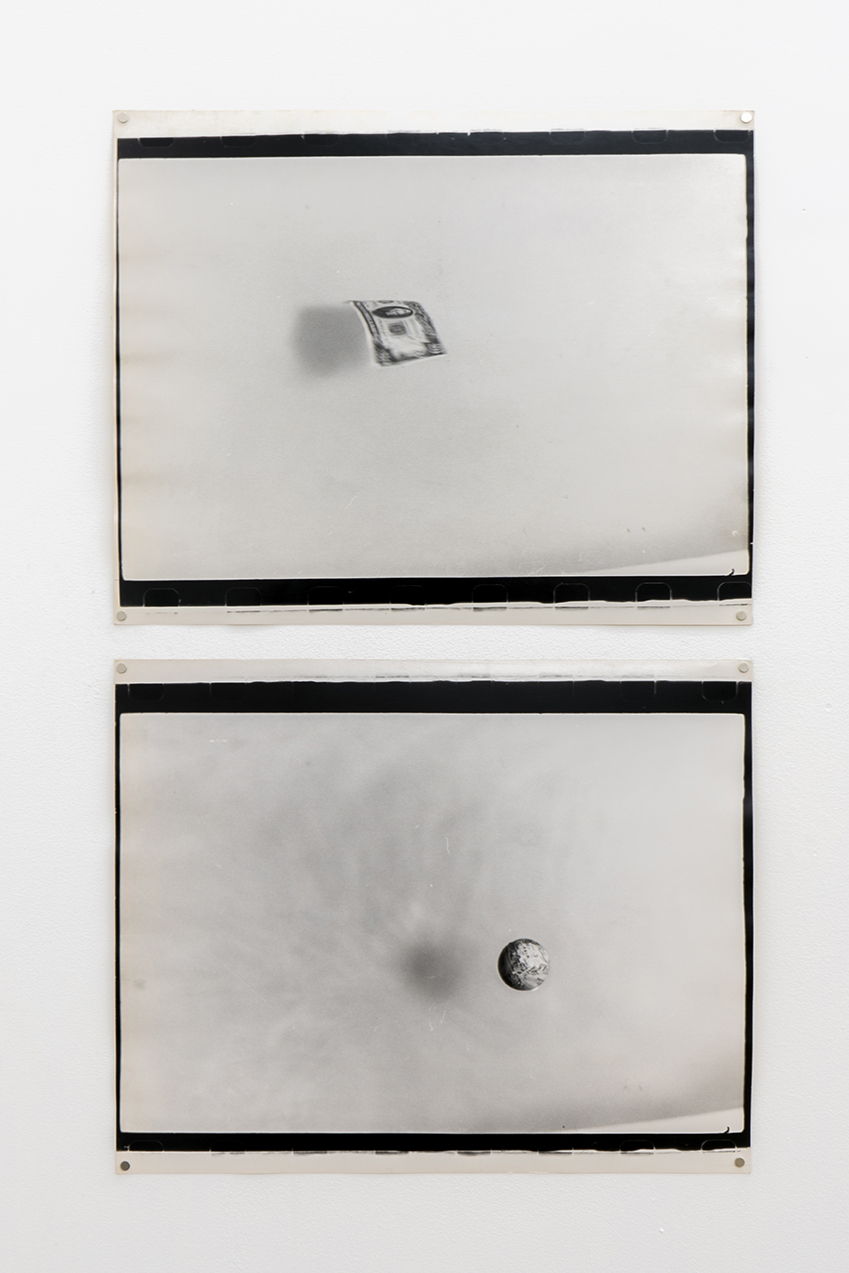

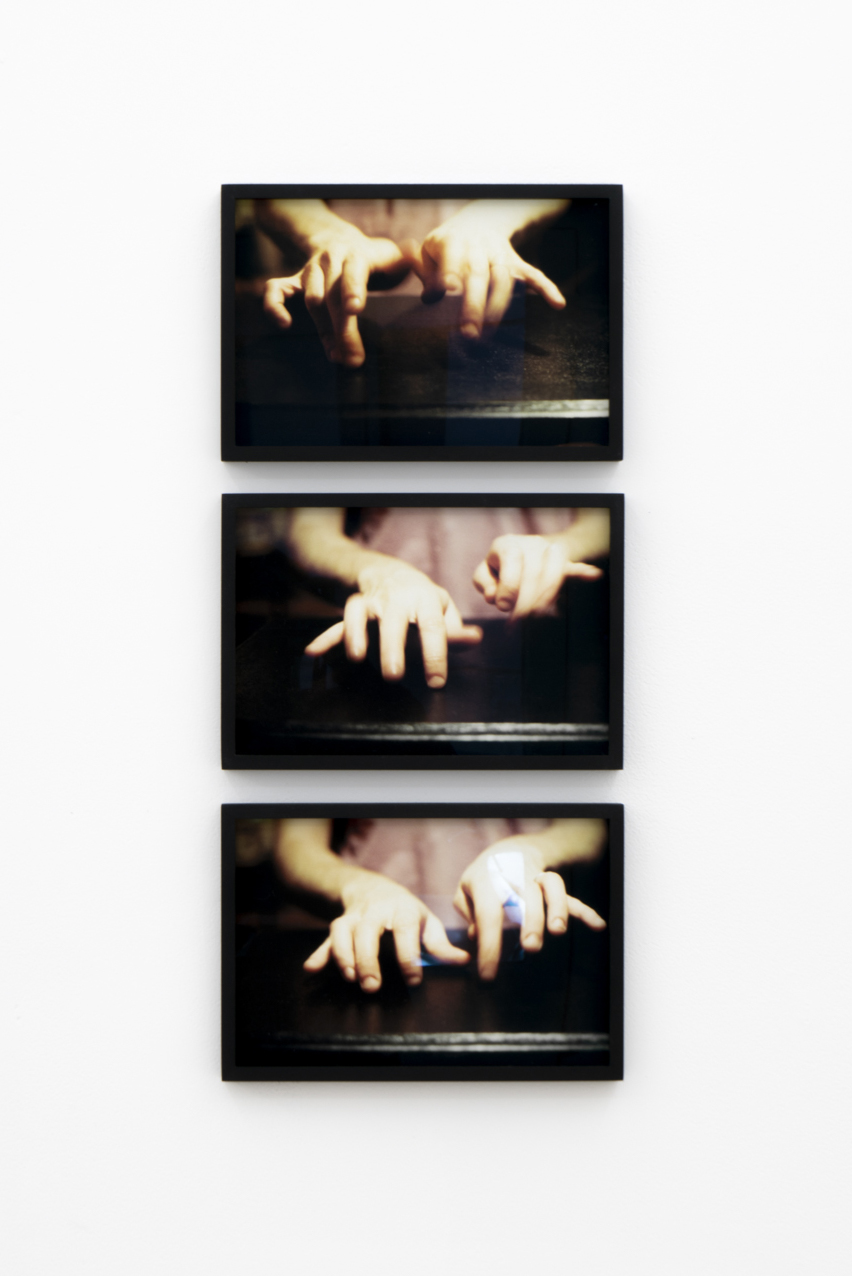

Exhibition view

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Exhibition view

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Exhibition view

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Exhibition view

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Exhibition view

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Exhibition view

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Exhibition view

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Exhibition view

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Exhibition view

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Exhibition view

Tim's ruler

Tim Maul

Exhibition view

EN

“The act of looking has no age - your eyes stay the same all your life.”

Jacques Derrida

Richard Dailey : You are an artist, another is Donald Judd, who writes compelling art criticism, perhaps in some part due to your long experience as a teacher. You are also perfectly au fait, with your own slant on the art-world zeitgeist, and deeply anchored in your time. Can you comment on your relationship to language, and the connection between producing art criticism and making art?

Tim Maul : I plowed through Judd’s entire writings a few years ago, an impossible person who thought the world owed him a living (I love his art). Villains included Count Giuseppe Panza (for good reason) and ‘bad fashionable’ painters Salle and Schnabel, naturally. In my final year at SVA (1972-3) a friend would circle words in Artforum and use them in critiques. He ended up in fashion. Every artist I admired wrote and I began writing inelegant reviews for Flash Art, an influential publication at that time. I wrote one on John Wesley a painter Judd actually admired and collected also an instructor of mine at SVA. Wesley lived near me in the West Village and told me he liked the review and that he had taken peyote with Judd. I hoped that writing would help me gain access to the art world beyond the gallery front desk, and it did/does. I am unsure what direct influence my criticism has on my own art, although researching an individual’s tenacity and perseverance serves as a positive example of something. The language around difficult art has been in both parts thrilling and preposterous, bar-stool philosophers at Max’s competed for Leo’s attention during very thin times. I once saw Laurie Anderson in a sweatshirt that read ‘TALK NORMAL’ so I try. You cannot control an artwork’s reception with a public unless you stand next to it and tell people what to think (which may make a good artwork in itself). Is art speak still spoken at art fairs? I cringe at the idea of having a white-collar ‘practice’, I want to drift and dream in what I do. My dentist maintains an excellent practice but I would prefer that he didn’t drift or dream.

RD : Even as you have always been somewhat shy of the NY art scene, everyone knows you, or at least knows who you have been for a few decades now; and more than your fastidiousness about “messiness,” perhaps your integrity distinguishes you. So today your highly alembicated photos may puzzle as much as they attract, causing us to think. To what extent, if any, do you think your photos invite conceptualising?

TM : During the 80’s my photographs were slow art in a feverish historical moment. There were a lot of events and parties and I benefited from the competitive buzz around artists my age and younger-everyone was hustling something, a band, a space, a little magazine, or their own art. Gallery openings resembled nightclubs and nightclubs started looking like gallery’s. I met Leslie Tonkonow during this time, she ‘got’ my photographs. I had a low-intensity social drive and the tyranny of the art ‘scene’ was an obvious extension of high school, but inclusion within a productive interesting clique didn’t hurt. However I never considered myself a bohemian, romantic, or member of anyone’s family except my own which was enough of a challenge. But I managed to get my art out there locally, in northern Italy, Antwerp, and later in Ireland. I didn’t have a brand. Conceptualizing? Its an achievement to get someone to look twice at an artwork. Photography attracted me because it was portable and democratic with everyone having some sort of experience with the medium. A camera transforms a fact into a fiction and the print or copy retains its unearned trust. We engage with photographs differently than paintings, I ‘look’ at paintings but I ‘read’ photographs. I’ve noticed that in a museum I immediately check when a painter was born but with a photograph in the same context I rarely do.

RD : Are photos inherently narrative, or does photographic narrative require some special presentation to bring it out, such as dyptics or juxtapositions?

TM : Rauschenberg said narrative was ‘the sex of painting’. Sequence and groupings of images may better demonstrate the passage and fragmentation of time. When working with a set of images I attempt to arrange marriages between pictures with the real source of fascination being the slot between prints on either the wall or page. A single image compresses narrative relative to content (I’m still working on this). ’Story’ art is only recently being recognized as the springboard to the ‘Pictures Generation’. I assisted Bill Beckley in the mid-70’s who put fictional texts directly into his assemblages of large color photographs emulated by ‘PG” deities Barbara Kruger and Richard Prince. We lost my brother Michael in 2020 who drew a daily cartoon saga which included precise notations of times and dates within every panel. He was one of the first individuals to be designated autistic and my own art is not that different than his.

RD : « Tim’s ruler », which you added recently to give Florence Loewy a sense of your photos’ scale, fascinates me as the kind of breezy contemporary gesture that feels exactly perfect, and might be construed as a nod to Marcel Duchamp’s “3 Standard Stoppages;” at the same time it somewhat resists Duchamp’s jokiness. “It’s a joke about the meter,” Duchamp glibly noted about his piece. What were you thinking when you included your ruler qua meta-text/image?

TM : The inclusion of my ruler was simply to give Florence an idea of scale. It seems to amuse you and I remember Robert Smithson being ‘unamused’ at Duchamp’s chess playing which he felt harbored ‘aristocratic connotations’ along with his sarcastic praise of American plumbing. Duchamp’s ‘stoppages’ were altered straight-edges almost identical to the one at the base of Durer.’s ‘Melancholia’, which leads to Jasper Johns. I am not sure if John’s many rulers are to scale but they appear throughout his work, frequently at the canvas edge. What is he measuring here? Or is he attempting to instill a degree of real-world order upon his desperate allegories of transference and loss?

RD : In a 1982 article in Artforum on Barnett Newman’s “Who’s afraid of red, yellow and blue?”, Michel Foucault says: “For a work of art is made of nothing but the esthetic judgments interpreting the history to which they belong.” It is a statement very much of its time, which is also partly your time. Do you agree, disagree or does the statement leave you indifferent?

TM : Newman’s heroism is beyond my capabilities. I agree in general with Foucault’s quote, its very ‘1982’ when art, to paraphrase Joe Maschek ‘forgot history’. But does it apply to Banksy, KAWS and NTF’s? I suppose it must.

Tim Maul (via email)

Richard Dailey is a writer, artist and filmmaker who divides his time between Paris and le Lot.