Biomimético-imago

| Gallery

Caroline Reveillaud

Biomimético-imago

Caroline Reveillaud

Biomimético-imago

Caroline Reveillaud

Exhibition viewFR

Dans les volutes du papier marbré, se dessinent des cours d’eau.

À la Galerie Florence Loewy, des ruisseaux affluent : ceux que Caroline Reveillaud a pu observer depuis 2022 et qu’elle fait resurgir ici, pour cette exposition. Au creux de leurs lits, vit un animal silencieux et discret : le bivalve d’eau douce, sentinelle de nos écosystèmes. Ce témoin de notre histoire a traversé avec patience les âges de la Terre et recouvre avec peine nos territoires actuels.

Dans ses précédentes expositions, les films, sculptures et éditions de Caroline Reveillaud interrogeaient nos rapports aux représentations issues de l’héritage moderne qui parcourt l’art et son histoire. Pour l’exposition Biomimético-imago, l’artiste opère un déplacement : elle s’éloigne de ce que produit l’art et se tourne vers ce que produit le vivant. Elle s’intéresse à l'idée d’une image sensible[1] : une pré-image formant un espace intermédiaire, où “sujet” et “objet” n’ont de cesse d’interagir. Une image qui ne serait plus une représentation fixe et plane, mais une forme élastique et plastique. Un sas avant l’image, un réseau de strates dynamique et organique, une somme de relations.

Les bivalves nous informent sur la qualité de nos cours d'eau, sur l’histoire de la Terre, celle de notre culture et de notre économie, ainsi que sur les écosystèmes fragiles et en péril à l’heure de l’écologie contemporaine[2]. On les retrouve également au cœur de nos représentations dans le domaine des sciences, celles-là même qui ont contribué à l’élaboration de l’objectivité[3] scientifique. L’artiste nous invite à envisager cet animal et ses espèces comme un catalyseur, un nœud dans l’espace et dans le temps, qui constitue cette image avant l’image et élabore une écologie qui lui est propre. Les deux pieds avertis dans les rivières et entourée de veilleur.euses éclairé.e.s (chercheur.euses, responsables de collections ethnographiques et zoologiques, écologues, naturalistes, biologistes, scientifiques, etc.), l’artiste nous donne à voir cette moule d’eau douce comme une image sensible, qui nous éclaire sur la teneur de nos rapports au vivant.

Pour sa quatrième exposition à la Galerie Florence Loewy, Caroline Reveillaud présente trois sculptures à hauteur de regard. Leurs formes empruntent au cabinet de curiosités, au lutrin ; des dispositifs qui ordonnaient autrefois les collections. Elles évoquent l’avènement du naturalisme moderne au XVIIIe siècle, période charnière où l’observation minutieuse du vivant devient méthode, où la connaissance passe par la mise en vue (truth-by-nature). Les dessins naturalistes instauraient un rapport direct entre l’œil et le sujet : on montrait pour apprendre, on rassemblait pour comprendre. Avec Biomimético-imago, l’artiste réemploie cette économie du regard, en prolongeant jusque dans la fabrication de ses sculptures des techniques empruntées à sa pratique de la reliure.

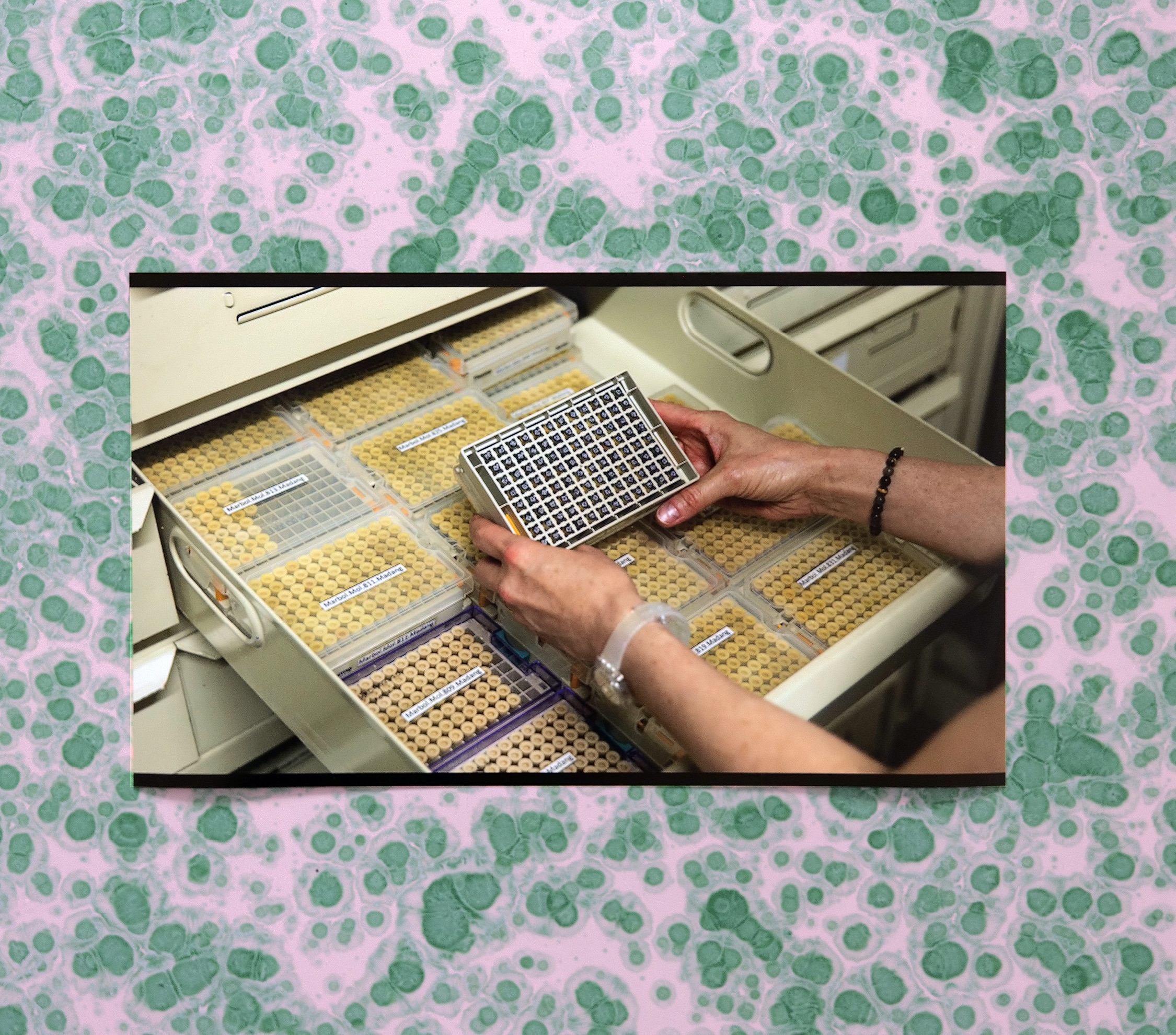

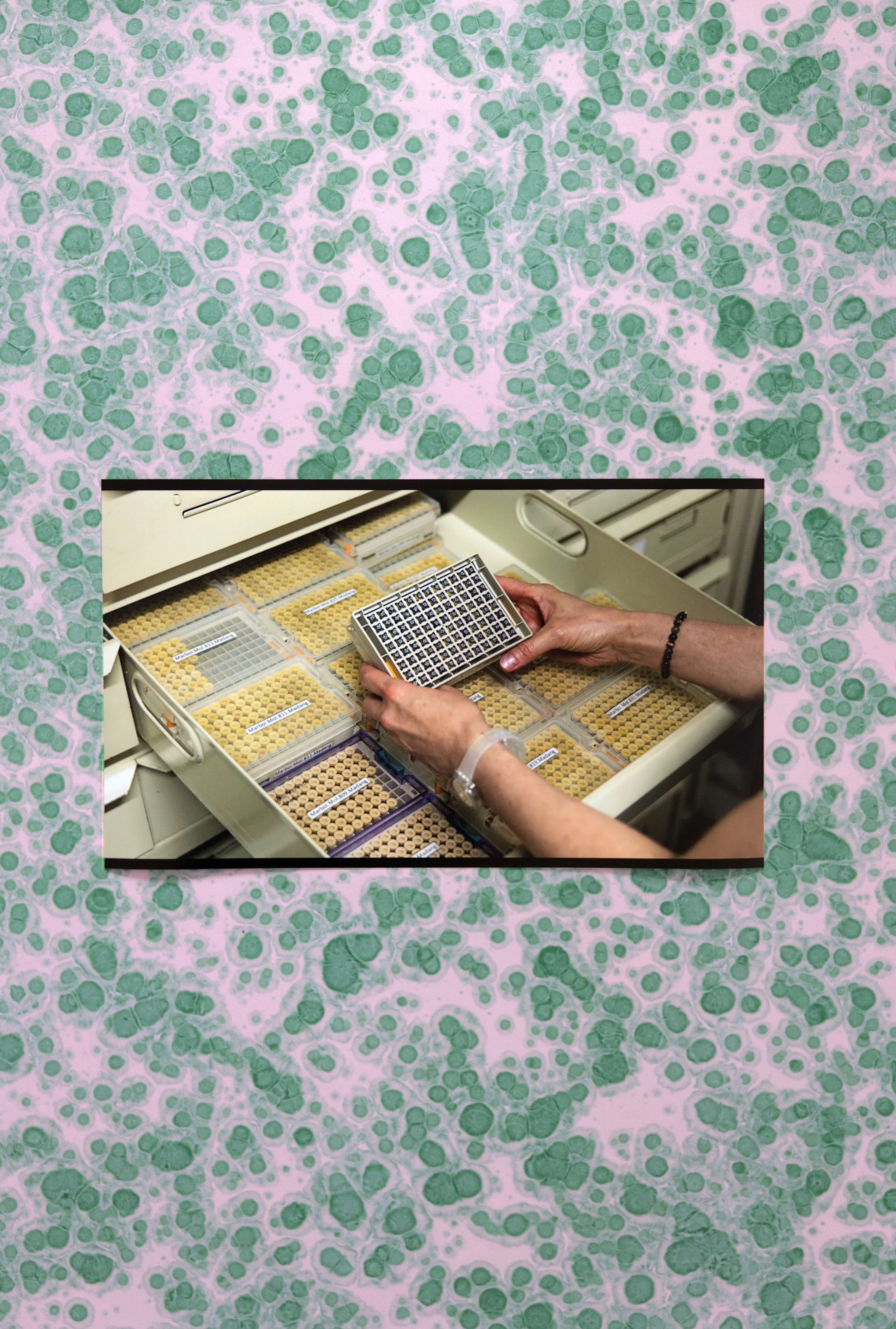

Si son film éponyme ne sera présenté sous la forme d’images en mouvements qu’en 2026, l’artiste montre ici sa version sculpturale, composée de trois espaces distincts. À la manière de bandes filmiques, ces assemblages d’objets hétéroclites composent des images fragmentaires. Un premier chapitre évoque le musée, ses collections et le dessin d'après nature. Sont présentés, un ouvrage naturaliste, une tabatière victorienne, des gravures et des anodontes des cygnes. Un second chapitre nous conduit au laboratoire, où la vision et la connaissance sont augmentées par la biologie moléculaire et la reconstruction d’images en 3D. Y apparaissent des disques de machines à rayons X et un picking tray – cette petite coupelle quadrillée utilisée pour compter et séparer différents spécimens. Enfin, un troisième chapitre nous mène sur le terrain de l’observation, des associations et des plans de préservation. On y trouve une boîte de mise en rivière de mulettes juvéniles réalisée à partir d’une armoire bretonne[4], ainsi que des images témoignant de ces pratiques participatives.

Les trois sculptures préfigurent un geste inaugural qui renvoie au récit de Pline l’Ancien sur le mythe fondateur de la peinture : la première image naît du contour d’une ombre projetée sur un mur, produisant une tension entre anticipation et représentation. Dans cet environnement liminaire où plusieurs temporalités coexistent, nous devenons les observateur.rices d’une œuvre sculpturale qui suggère une œuvre filmique sans la dévoiler. Au cœur de cet entre-deux se tapit la promesse de quelque chose qui vient, comme cette image sensible, complexe et déterminante, qui était peut-être là depuis le début.

Thibaud Leplat

EN

In the swirls of marbled paper, waterways appear.

Water courses through the Galerie Florence Loewy as Caroline Reveillaud evokes the different rivers and streams she has observed since 2022, diverting them through the exhibition space. On their sandy beds lives a silent and elusive animal, the bivalve freshwater mussel. This sentinel of our ecosystems has patiently traversed the Earth’s different ages, and painfully clings on in the landscapes and territories we have shaped.

In her previous exhibitions, films, sculptures and artists’ books, Caroline Reveillaud has explored the relationships to the representations of modernity that are woven into art and its history. For the exhibition Biomimético-imago, she changes tack, moving away from the things produced by art and instead taking up the things produced by the living world. She is particularly interested in the idea of the sensitive image:[1] a pre-image that forms an intermediary space where “subject” and “object” interact continuously; an image which is not a fixed and flat representation but an elastic, material form; an antechamber to the image, a network of dynamic and organic strata, a sum of multiple relations.

In the context of contemporary ecology, bivalve mussels provide us with information as to the quality of our water, the history of the Earth, our culture and our economy,[2] as well as fragile and endangered ecosystems. We also find them in the representations circulating in the scientific field, the very same ones that have contributed to the development of scientific objectivity.[3] Caroline Reveillaud invites us to consider this species and its cousins as a catalyst, a node in space and time that constitutes the image before the image whilst developing its own ecology. With both her feet firmly planted in the river bed, and surrounded by expert observers (researchers, ethnographic and zoological collection curators, ecologists, naturalists, biologists, scientists, etc.), she reframes the freshwater mussel as a sensitive image that can shed light upon the nature of our relationship to the living world.

For her fourth exhibition at Galerie Florence Loewy, Caroline Reveillaud presents three sculptures that are displayed at eye-level. Their forms recall those of a cabinet of curiosities or a lectern, devices that once ordered precious collections and repositories of knowledge. In this way, they evoke the emergence of modern naturalism in the 18th century, a key period during which close observation of the living world became a method in its own right, and in which knowledge became closely related to display by way of the notion of “truth-by-nature”. Naturalist drawings instituted a direct relationship between the eye and the subject: if things were to be taught and learned, they had to be shown; if they were to be understood, they had to be assembled. With Biomimético-imago, Caroline Reveillaud reactivates this visual economy, extending it into the very production process of her sculptures, where she redeploys techniques from her practice of bookbinding.

Though the film which gives the exhibition its title will not be presented until 2026, Caroline Reveillaud here presents a sculptural version of it across three distinct spaces. Assemblages of miscellaneous objects make up fragmentary images that recall filmstrips. A first chapter evokes the space of the museum, with its collection and its drawings based on the observation of nature. It features a naturalist tome, a Victorian snuffbox, a series of engravings and a number of swan mussels. A second chapter unfolds in a space akin to a laboratory, where molecular biology and 3D-imagery promise to expand vision and knowledge alike. Discs from an X-ray machine appear alongside a picking tray – a gridded dish used to separate out and count different specimens. A third and final chapter turns its focus onto observation, activism and preservation. Here we find a box designed for reintroducing young freshwater pearl mussels into rivers that has been fashioned from a traditional Breton wooden armoire,[4] as well as images documenting these participative approaches.

The three sculptures prefigure an inaugural gesture which draws on Pliny the Elder’s story of painting’s foundational myth – the first image as a trace of the outline of a shadow on a wall – which introduces a tension between anticipation and representation. In this liminal environment where several different temporalities coexist, we become observers of a sculptural work which suggests, without revealing, a second filmic one. At the heart of this in-between lies the promise of something to come, of that complex and decisive sensitive image that has perhaps been there from the very beginning.

Thibaud Leplat

[1]

Emanuele Coccia, La vie sensible, Rivages, 2018

[2]

Économique (industrie du bouton de nacre, perliculture), culturelle (artefacts) et sur les écosystèmes fragiles et en péril de notre histoire écologique contemporaine (plan nationaux d’action pour la préservation de mulettes).

They are linked to the economy by way of the production of pearls and opalescent buttons; culture through the artefacts created using their shell, to the fragile ecosystems of our contemporary history (national programme for the preservation of freshwater mussels).

[3]

Lorraine Daston, Peter Galison, Objectivité, 2012

[4]

Le programme LIFE pour la réintroduction de mulettes perlières en rivière de Bretagne arrivant à sa fin en 2021, l’écologue Ronan Le Mener réalise à partir de bois récupéré d’une armoire bretonne familiale des boîtes imputrescibles pour la mise en rivière des mulettes juvéniles.

As the LIFE programme for the reintroduction of freshwater pearl mussels into rivers in Brittany came to an end in 2021, ecologist Ronan Le Mener used wood salvaged from a traditional Breton wardrobe that belonged to his family to make rot-proof boxes for releasing young mussels into rivers.